At the heart of venture philanthropy is an engaged approach with the funded organisation. Capacity building of social purpose organisations is one of the main activities funders in this region engage in. Ideally what is provided by the social investor or resource provider matches what is needed on the side of the social purpose organisation. The social purpose organisations’ needs tend to come from internal parameters in the social purpose organisation, e.g. the development stage of the organisation, the management team, its social mission, business model and growth plans as well as the external environment, which shapes the entrepreneurial eco-system, economic stage of the country and the role of the government. Social investors then have different in-house capabilities to support capacity building and hence need to draw on third-party providers either paid, low- or pro-bono. This requires the venture philanthropy organisation to manage the third-party interactions.

Ideally the outcome is capacity building through a variety of tools such as strategic support, professional services and physical infrastructure, which aims to create real value for the social purpose organisation by helping them to achieve their social missions and value for the social investor or resource provider by increasing their impact.

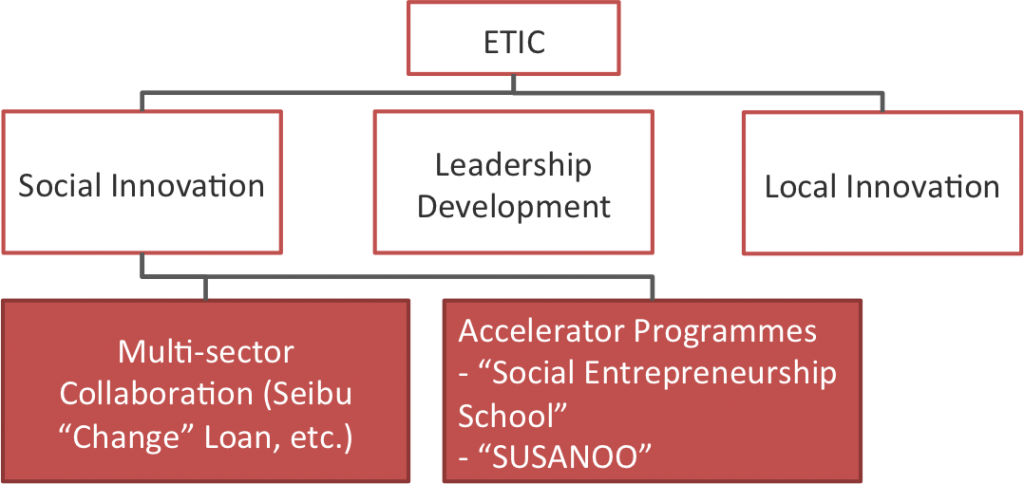

Here, we explore the mission and practices of Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities (ETIC), one of the oldest organisations in Japan supporting social entrepreneurship, with particular attention given to ETIC’s Social Innovation Department, the umbrella body responsible for ETIC’s core suite of programmes (see Figure 1). By offering a diversified portfolio of capacity building measures to Japanese interested in social entrepreneurship at any stage – through its internship placements and incubation programmes – ETIC has established itself as a launch pad for Japanese youth, students, working professionals and corporations.

ETIC’s Organisational Portrait

Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities (ETIC) was founded in 1993 by Haruo Miyagi, then an undergraduate student at Waseda University, as a nation-wide network of student entrepreneurs. Over its first three years, ETIC arranged 200 seminars and study sessions for Waseda University students interested in becoming entrepreneurs and hosted conferences and symposiums (in 1993, the Student Entrepreneur Liaison Conference and in 1994, Shushoku-chotto-matta – “Wait before deciding your employment”- Symposium). Such events drew more than 300 students from 10 other universities and attracted media as well as governmental attention.[1]

Following its initial student-led entrepreneurship events, in 1997 ETIC launched its “Entrepreneurs Internship Program,” a 6-month initiative that placed interested students in internships mainly with IT start-ups. Over subsequent years, ETIC further expanded its support activities for entrepreneurs in Japan, by establishing its Social Venture Center in 2002 as the coordinating body for all of ETIC’s partnerships, training programs and initiatives. There were several reasons that ETIC decided to focus on the development of social entrepreneurs. At the outset of ETIC in the mid-90’s, the ‘dotcom bubble’ produced many tech start-ups and supporting organisations, like venture capitalists, in Japan. In light of the burgeoning industry, ETIC’s board thought “as a non-profit organisation, we should pioneer other fields where social demand is high but the market has not existed yet.”[2] After the dotcom bubble burst in 2001, many entrepreneurs involved in ETIC’s activities started considering what they could do for the benefit of society using their business platforms and mindset. In 2011, ETIC’s activities were further catalyzed by another historical circumstance: the Great Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, which moved ETIC to launch a new fellowship programme to serve needs in the affected regions of Japan.[3]

As of 2015, with 43 full-time staff and 32 part-time staff and interns,[4] ETIC through its wide range of activities has supported and trained over 300 young social entrepreneurs in Japan. Of these, 22% were in the field of education/nurturing, 20% were in local community development fields and 13% were in social welfare/health/medical fields.[5] Through its various matching programs, ETIC has additionally sent more than 7,000 young Japanese students and professionals to areas of business and social innovation where new solutions to social problems are being developed.[6] Ultimately, more than 85% of the entrepreneurs that ETIC has trained “from scratch” have continued to engage in social entrepreneurship in some capacity, thus contributing to the growing entrepreneurial community in Japan.[7]

ETIC’s Programmatic Structure (Figure 1)

For ETIC’s “Social Innovation” arm (which handles ETIC’s core suite of programmes for social entrepreneurs), the total annual budget is US$ around 2 million (FY2015), around 80% of which comes from corporations (domestic and international) and 20% from the Japanese government.

ETIC does not usually charge fees for its programmes, but due to ample subsidization and donations from donors and partners, individual participants usually do not have to pay to attend or pay a nominal portion of the fee.[8]

ETIC’s mission, evolving role and theory of change

ETIC perceives social entrepreneurship as a salve to pressing social issues in Japan that are otherwise largely overlooked or passed over by traditional, state- or market-delivered solutions. ETIC notes that the “strong and rapid economic development [in Japan after the second World War]” was commonly understood by national leaders as signifying social change as well. In the light of the 20-year recession that followed the period of growth, more recent generations of Japanese have not necessarily shared this view with their leaders. Whereas once, most Japanese youth aspired to join mainstream white-collar professions (like medicine, law and civil service), ETIC saw (and continues to witness) an increasing number of youth galvanized into pursuing careers that address pressing social issues in new ways.[9]

As mentioned above, a watershed moment for ETIC – as well as for the country and greater region – was the Great Tohoku Earthquake and tsunami that struck various parts of Japan in 2011, devastating vast swathes of the country, catalysing a major nuclear incident and leaving many Japanese communities in need of disaster relief and long-term recovery assistance.[10] As ETIC remarks, the disaster triggered increased attention on community participation across various sectors of Japanese society: “[The] consciousness of Japanese youth changed after the earthquake…more professionals moved into the social sector and more [government bodies] and corporations considered what they could do,” approaching ETIC for various collaborative projects.[11]

ETIC perceives its overall value-add as the unique nature of its diversified business portfolio. Its wide range of offerings for social entrepreneurs (whether they be students, professionals or aspiring and seasoned entrepreneurs) rests on two capacity building objectives:

- To send students/professionals to work in startups and non-profit organizations (or anywhere innovation and challenges are taking place) through its Entrepreneurs Internship Programme, Challenge Community Project, Disaster Recovery Leadership Project);

- To develop and support entrepreneurs through its various Incubation Programmes for Social Entrepreneurs.

Following from its above origins, ETIC’s initial objective was to develop social entrepreneurship knowledge among university-age Japanese and provide support to youth who aspired to engage in solutions to social issues. ETIC has had wide-spread success, in this respect, and can point to strong contingents of Japanese youth around the country who it has, through its various matching processes/programs, connected to social ventures and community organizations where “innovate on and challenges are taking place”. [12]

In that context, ETIC pursues two avenues for its theory of change. The first core activity revolves around leadership development for social enterprises, with less emphasis on the business planning or operational support for the enterprise. They believe such an approach can assist young Japanese clarify their own entrepreneurial aspirations and amplify entrepreneurship nationwide by helping young entrepreneurs form communities and ties to each other. Connections to ETIC’s mentors (senior entrepreneurs) assist in developing these connections and fostering communal spirit.

A related activity extending beyond this core is ETIC’s fellowship programmes, which send young, high-potential Japanese to internships in start-ups. This has the reciprocal effect of both providing start-ups with a strong workforce and helping the interns gain skills in an entrepreneurial environment that they can further develop in other contexts (including starting their own businesses). This focus on fostering and amplifying entrepreneurial aspirations is reflected in the success rate of the programme, which has more than 85% of trained entrepreneurs continuing in their enterprises.[13]

ETIC’s core – building capacity of social entrepreneurs at different stages

ETIC’s most well-known programmes are its Entrepreneurs’ Internship Programme and Social Entrepreneurship School, the first of which is widely known among Japanese college students who have interests in social businesses or venture start-ups, and the second of which is recognized as a gateway to successful social entrepreneurship in Japan, having graduated 82 alumni since 2001. A short list of ETIC’s most well-known programmatic offerings include:

- 1997: Entrepreneurs’ Internship Program: ETIC’s longest running internship program, which since 1997 has produced 150 successful entrepreneurs (out of a total 2,745 participants). Feedback from the programme has been that “business development experiences” from these internships encourages interns to take more proactive roles in venture companies and the social sector and also helps them attain positions in traditional firms.[14]

- 2002: Social Entrepreneurship School: This initiative focuses on providing foundational training for social entrepreneurs to conceptualize business purpose and clarify strategy. The Bootcamp component provides entrepreneurs with lectures and interactive sessions from senior mentors and peers to develop business plans with a social impact focus. Virtual Board Meetings (VMBs) then enable entrepreneurs to review their business plans with senior mentors and specialists from ETIC’s network (comprising about 200 individuals). Meanwhile, 1-on-1 Mentoring sits budding entrepreneurs down with more experienced, senior entrepreneurs for individual mentoring sessions twice a week.[15] Sayaka Murata, founder of the Kamonohashi Project, was one of the first batch of graduates of this programme.[16]

- 2011: Disaster Recovery Leadership Project: Over 200 participants have gone through the fellowship programme to work in local grassroots recovery organisations in Tohoku region of the country; of these >200, around 60% remained in Tohoku after completion of the fellowship to begin their own social entrepreneurship initiatives.

- 2014: Social Startup Accelerator Program (SUSANOO): Based on the “Lean Start-up” approach originating in the IT sector, in 2014 (its initial year) the SUSANOO pilot programme received 57 applications and chose 14 finalists to undergo its 6-month program involving weekly bootcamps, social events and networking functions.[17]

ETIC notes that as a facilitator of partnerships between funders and investees (e.g. individual entrepreneurs and social enterprises), it strives to keep “the relationship flat between [the social purpose organisations] and funders”, often inviting funders to ETIC’s accelerator programmes to communicate directly with entrepreneurs they support and helping to organise subsequent meetings if both parties are interested in further collaboration.

Hands-off support

ETIC notes that it does not hand-hold its social entrepreneurs by providing operational, financial or governance support – instead, they adopt a “more hands-off” model based on mentoring and coaching that helps entrepreneurs grow independently: “We support their growth [so that they can] function independently and do not provide direct support [on operations, public relations etc.].” However, when these resources are needed, ETIC does “coordinate with [entrepreneurs] to connect them with these resources [like the senior entrepreneurs/mentors],” as in the case of the Seibu Business Development loan (details below), in which ETIC collaborated with a commercial bank to design a bespoke financial tool tailored to the needs of social entrepreneurs.[18]

ETIC perceives the capacity building support required by early-stage entrepreneurs as markedly different from that needed by their mid-growth or already established counterparts. For early-stage entrepreneurs, ETIC focuses on coordinating resources and facilitating mentoring relationships between senior and junior entrepreneurs; for those at growth-stage, ETIC additionally helps them assess their value propositions to potential markets and diversify their network so that they can access a variety of resources and partnerships.

While ETIC has a common set of criteria it uses to evaluate candidates for its programmes (namely, their capacity to solve social problems; their growth potential and sustainability of business concept; and their commitment and ability of the management team), ETIC notes that its wide scope of programmes necessitates tailored acceptance criteria for each programme and its objectives.

CB Tools for development & support of social enterprises (SEs)

Most of ETIC’s capacity building efforts are conducted through its “Social Innovation” arm (see programmatic diagram above), including both long-running and short-term initiatives:

- Social Entrepreneurship School: Provides capacity building in the form of individual entrepreneurial skills development beginning with conceptualization stage and mentorship.

- Social Startup Accelerator Program (SUSANOO): Provides capacity building by giving entrepreneurs a networking platform to, develop business model, pitch, and be exposed to the “Lean Start Up” model.

- Leadership Development Programmes: Through partnerships with external agencies and corporations (including, respectively, the Japanese Cabinet office and JPMorganChase Foundation), provides overall leadership training in entrepreneurship at mid-growth stage.

- Seibu Social Business Development Support Loan (“CHANGE”): Since 2013, this new loan product has supported growth-stage social enterprises in the greater Tokyo area by providing financial and non-financial support. Through a partnership with Seibu Shinkin Bank (the leading credit union in Tokyo) and Nippon Foundation (the largest foundation in Japan) the “CHANGE” loan – an uncollateralized loan with fixed interest rate (of 0.1% per annum under 5 million JPY or 1.0% under 50million JPY) – is designed for social businesses to put towards their operations and infrastructure. Organizations who take the loan additionally benefit from individual management counseling and young resource matching support provided by ETIC. As of May 2015, 28 organizations had taken advantage of the “CHANGE” loan.

In addition to the individual initiatives above, ETIC often organizes Virtual Board Meetings (VBMs) (previously mentioned under “Social Entrepreneurship School” on pg. 5) depending on the needs of the entrepreneurs it supports. VBM, a discussion for reviewing entrepreneurs’ business issues with senior mentors, is one of ETIC’s common approaches to matching entrepreneurs with its 200+ mentor network. In the matching process, ETIC evaluates who could be the most suitable mentor for an individual entrepreneur taking into account their respective field/industry, stage of development and personalities.

For entrepreneurs, there are many benefits to participating in VBMs. Most notably, with 2-3 senior mentors’ feedback, entrepreneurs can see their business issues from a more neutral point of view and gain a more objective, longer term perspective on their activities. Such an environment (that allows objective introspection) is rather difficult for a social enterprise to build for itself in early stages. Secondly, though the senior mentors are not real management members, through VBMs entrepreneurs have the opportunity to learn about how to leverage the abilities of their board members, one of the most important aspects of their organizational growth. VBMs may also potentially be an opportunity for social enterprises to recruit a new board member if mutual interest is established over the course of the discussions. This was the case for Konuma Daichi, CEO and Founder of Crossfields, who notes that his organization “obtained two board members through VBM. Both of them were highly committed to co-developing our business core.”

Extending the core – building Japanese social innovation with stakeholders

ETIC’s broad spectrum of programmatic and partnership offerings positions it uniquely in the Japanese landscape as an established nexus of, stakeholder in and contributor to the ongoing development of social entrepreneurship in the country. Throughout its evolution, ETIC has also focused efforts on creating a welcoming environment for social entrepreneurship in Japan, by building its network of industry and academic contacts and presence among communities in Japan, with 62 local community organisations, 21 universities, 7 central and local governments and 30 private companies and foundations across the country now on its roster of partners.

Due to this the social entrepreneurship objectives, ETIC’s activities in the wider social fabric of Japan demonstrate ETIC’s broad reach to SMEs, the government and young professionals:

- GoldmanSachs SME Management Innovation Programme: This 6-month internship program for university students sends them to internships in selected SMEs. In its initial year (2014), 50 SMEs across Japan received interns through the programme.[19]

- ETIC research agenda on internships with Japanese Ministries: ETIC collaborated on research that promoted the high educational impact of internships for Japanese students, developing policy recommendation principles that were subsequently included in policies of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.[20]

- MIGIUDE (Japanese for “right hand”) Fellowship Programme: This initiative puts young professionals/fresh grads in orgs supporting Tohoku earthquake recovery efforts. 14 participants (out of 161) became entrepreneurs in the area/region of Tohoku after the internship ended, demonstrating the interest among Japanese youth to engage in activities in which “business, working and living” in a local community are interlinked.[21]

Defining success of capacity building measures

ETIC is still trying to develop KPIs for capacity building, as “success” is difficult to gauge at their beneficiaries’ early and mid-growth stages. However, ETIC currently relies on metrics like the number of entrepreneurs supported and the business continuation rate of their programme participants. In the future, ETIC would like to develop a KPI related to how well they have assisted in fostering an entrepreneurial ecosystem – while, as they note “there is [as of yet] no clear indicator on this…it could be [measuring success of ETIC’s efforts in] matching of mentors and students or the amount of money or resources being exchanged” in ETIC’s entrepreneurial communities.[22]

Challenges

Over the more than two decades of supporting social entrepreneurship in Asia, ETIC has encountered and overcome a few challenges, mostly through its “Social Innovation” arm.

One of ETIC’s initial challenges was scaling up its activities in initial years and learning to utilize new resources and funds effectively as its activities gained momentum. For instance, over the first 8 years of ETIC’s Social Entrepreneurship School (2001 to 2009), the School was funded by only one corporation and sponsored only 5 entrepreneurs per year – “We didn’t know how to expand,” ETIC describes. However, in 2010 ETIC had a chance to partner with and receive additional funds from the Japanese Cabinet Office, suddenly bringing the number of entrepreneurs ETIC supported to 100 over a 2-year period (2010 and 2011). With the sudden exponential growth of its programme, ETIC moved quickly to adapt, changing its tracking system and the matching system between senior and junior entrepreneurs (e.g. using larger matchmaking events). In addition, ETIC changed the way it used its grants from the Cabinet Office, by first awarding each entrepreneur a base grant of US$5,000, then following with additional funding once the initiative had yielded initial positive results. On average, entrepreneurs received US$20,000 in total, with the upper end reaching US$50,000.

A second challenge ETIC confronted after its initial years came with the realization that the entrepreneurs ETIC had helped inspire to begin their own businesses (more than 300 at the time) were struggling once they graduated from seed-stage and entered more mature phases of growth. To address this issue of stunted growth, ETIC has been engaging partners to provide the particular sort of resources needed by mid-growth stage entrepreneurs. One example of this is the Seibu Bank “CHANGE” loan, which provides much needed financial support to growing entrepreneurs, augmented with ETIC’s non-financial capacity building support (see more details above in the “Capacity Building Tools” section). ETIC comments that it can be difficult to understand “the real needs of entrepreneurs at the growth-stage” but that ETIC does its best to match them with the appropriate mentors and organizations from ETIC’s 200+ mentor network (from the business and government sectors). While the Seibu “CHANGE” loan has been one achievement in matching needs to resources appropriately, ETIC is currently testing various types of other support programmes for mid-growth stage entrepreneurs with external partners like the Japanese Ministries and JPMorganChase Foundation.[23]

In sum

ETIC’s model for supporting social entrepreneurs rests on two pillars: the first, of developing and supporting entrepreneurs through training and resource matching and the second, of sending students and professionals to work or intern in start-ups. The Incubation Programmes for Social Entrepreneurs advances the first pillar of ETIC’s mission, while ETIC’s Entrepreneurs Internship Program, Challenge Community and Disaster Recovery Leadership Projects advance the second.

ETIC’s capacity building approach is “hands off,” focusing on developing leadership among Japanese students, professionals, and aspiring entrepreneurs. Collectively, ETIC’s wide array of programmes, targeted to these various social groups, seeks to “amplify” social entrepreneurship and build an ecosystem in Japan for social entrepreneurship.

[1] ETIC website, accessed 31 July 2015 at http://www.etic.or.jp/english/outline.html

[2] Email conversation with Mitsuhiko Yamazaki on 9 Sept 2015.

[3] ETIC website, accessed 31 July 2015 at http://www.etic.or.jp/english/outline.html

[4] ETIC website, accessed 30 July 2015 at http://www.etic.or.jp/english/outline.html

[5] Yamazaki, Mitsuhiko and Motoki, Yuko. “Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities (ETIC)”, Powerpoint Presentation 18 July 2015, p. 7

[6] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 3

[7] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[8] Note from ETIC on draft report, received 18 August 2015.

[9] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[10] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011 (Great Sendai earthquake; Great Tohoku earthquake)”, accessed online on 18 August 2015 at http://global.britannica.com/event/Japan-earthquake-and-tsunami-of-2011.

[11] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[12] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 4

[13] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[14] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 4

[15] “Entrepreneurial Training” Powerpoint, p. 12

[16] Conversation with Mitsu Yamazaki of ETIC on 17 June 2015.

[17] “Entrepreneurial Training” Powerpoint, p. 14

[18] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[19] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 5

[20] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 5

[21] ETIC. “ETIC English Annual Report Draft 2013/2014,” p. 4

[22] Conversation with Kensuke Sasaki, Mitsuhiko Yamazaki and Yuko Motoki on 17 August 2015.

[23] Email conversation with Mitsuhiko Yamazaki on 9 Sept 2015.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.