4 min read

- Even though government provides free and compulsory education for all, learning outcomes have not been optimal.

- We compare public and public providers through the lenses of affordability and quality.

- A public-private partnership model may be necessary to build a fully functional public education system

Sohail (name changed), a 17-year-old boy, was a grade 10 government school student living in a Tier 1 Indian city. Sohail had been promoted year on year to higher grades, thanks to the no failure policy, but worryingly doesn’t have mastery on many grade 3 and 4 level concepts. Fortunately, he is supported by a local education NGO where he receives remedial support.

Fast forward to 1.5 years later: His family went against the NGO’s advice and pulled him out of school. He started working for his uncle at a roadside kiosk. Today, at 23-years-old, he is still working at the key shack. More gravely, his former classmates say he consumes illicit drugs.

This rather depressing anecdote, that I am a first-hand witness to having been his teacher at the NGO, epitomizes the challenges our beleaguering public education system faces. Given the surge in private school education, which some believe is an antidote, I try to address if privatizing K-12 education is a step in the right direction.

Firstly, what is education?

Grossly simplifying what the diverse literature says, I define education as the acquisition of those skills that make an individual self-sufficient: financially, physically, emotionally and as a citizen of society.

By this definition, it should then be the responsibility of the government to be its guarantor.

How effective have government policies been?

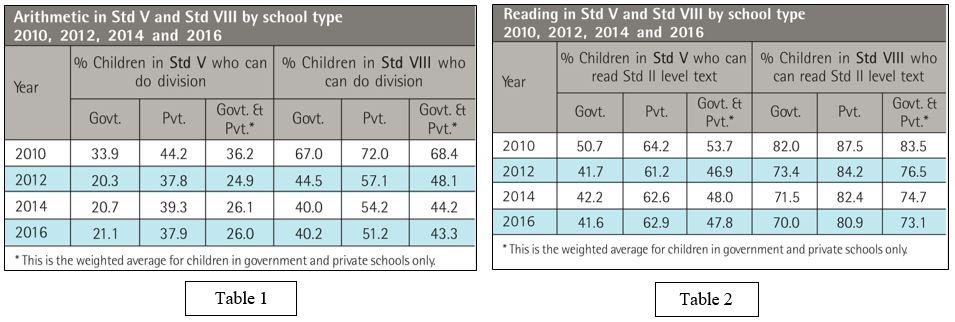

The ‘Right to Education Act’ 2009 mandates the government to provide free and compulsory quality education to all children (6-14 years). However, 7 years into the Act, the data on learning outcomes is quite discouraging (sourced from the ASER 2016 report).

Both tables speak to the falling learning levels in both reading and arithmetic. Nonetheless, it reflects better performance in private schools across the years which leads me to ask:

Is the private sector better equipped to provide K-12 education?

I shall evaluate both public and private providers through the lenses of affordability and quality.

Affordability

Even if education is free, there are hidden opportunity costs of attending schools (Tilak, 1996). For many poor families, children are income-generating sources. Parents need to have enough evidence of immediate benefit or receive monetary assistance to send children to schools. Some governments address this issue by offering free textbooks, meals, uniforms and vouchers[1]

However, ‘low-fee’ private schools within the state of Delhi charge anywhere between $10 to $18 (2011 exchange rate 1USD = 46 INR). If this is the case, then private schools by their very nature exclude a whole section of India’s poor who simply cannot afford them.

Quality

The biggest reason for student dropouts in India is an apparent ‘lack of interest in studies’[2]. Experts[3] use data (ASER’s data as a case in point) to argue in favour of private schools. However, others[4] warn against using this evidence as a case for ‘privatisation’ as a lot of ‘proxies’ for quality, better infrastructure as an example, are questionable.

Also, as the AVPN Funding with Education with Impact suggests, the variance can be attributed to a fall in the learning levels in government schools with private school levels staying constant.

What does this mean?

It seems obvious that even though the Indian government is constitutionally responsible to provide quality education, it is failing to do so. Even on a macro level, plummeting GDP spends (2.7%) are a cause for concern. In turn, the low-fee private sector is burgeoning out of this ‘opportunity’ caused by the government’s failure.

However, endorsing privatisation seems ill-advised. Testimony to this is what Nobel Laureate, Amartya Sen said, “India is the only country which is trying to get universally educated and universal healthcare through the private sector. Japan, US, Europe, China, Vietnam, Cuba, Hong Kong, Singapore, all saw the importance of the state in making education and healthcare widely spread and universal”

Perhaps, a public-private partnership model may act as a necessary bridge to build a fully functional public education system. In Dasra’s report, ‘Making the Grade’ highlights how the quality of education in public schools can be improved by strengthening the partnership between multiple stakeholders. For example, Muktangan, and Teach for India have adopted schools where the municipality has outsourced the funding and management of schools with an intent to share best practices across all public schools.

The crucial role of philanthropy is then to support this structured transition towards a functional public system that needs to become a reality for all Indian children sooner than later.

[1] Banerjee, A. and Duflo, E. (2011) Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking Of The Way To Fight Global Poverty New York: Public Affairs

[2] Govinda, R. and Bandyopadhyay, M. (2007) Access to Elementary Education In India

[3] Tooley, J. et al (2010) The relative quality and cost-effectiveness of private and public schools for low-income families: a case study in a developing country School Effectiveness and School Improvement http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09243450903255482

Tooley, J. et al (2011) School Choice and Academic Performance: Some Evidence From Developing Countries Journal of School Choice http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15582159.2011.548234

[4] Sarangapani, P.M. and Winch, C. (2010) Tooley, Dixon and Gomathi on private education in Hyderabad: a reply http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03054985.2010.495465