CSR offers an opportunity to transform education for the urban working poor

To download the original pdf, please click here

India’s working poor are spending their hard-earned money on private schools because they want a better future for their children. The harsh reality is that the schools are letting these parents and their children down.

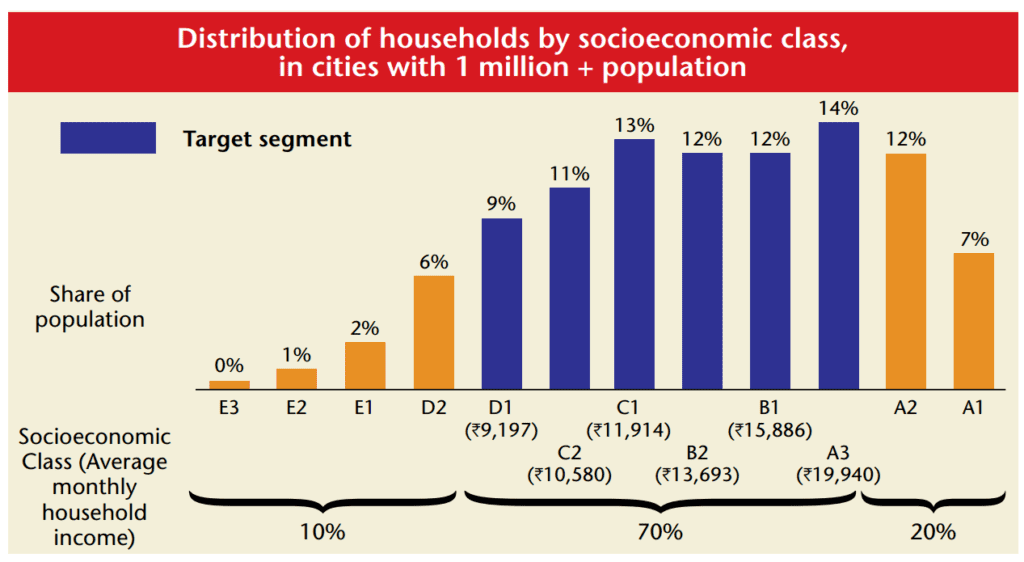

The numbers involved are staggering. Working poor households make up 70 per cent of urban India. This group includes those working as domestic help, drivers, office clerks, labourers, and petty traders etc. As much as 86 per cent of them are enrolling their children in affordable private schools (aps).

But the results are abysmal. India’s private schools are churning out students who have rote-learned their way through the grades and do not have the skills necessary to secure the kinds of jobs for which their parents invested so much. According to a survey by Educational Initiatives, only 35 per cent of ninth and tenth graders can read at a level expected of a fourth grader, with similarly poor learning outcomes in both government schools and APSS. Another study found that India ranked 73rd (just above Kyrgyzstan) in a study of 74 countries on mathematics, reading, and science.

Even more worrying is the fact that no one is focusing on improving the quality in private schools. CSR funding and philanthropy are helping government schools and those run by NGOs, while private schools (and the millions of low-income children in them) are neglected.

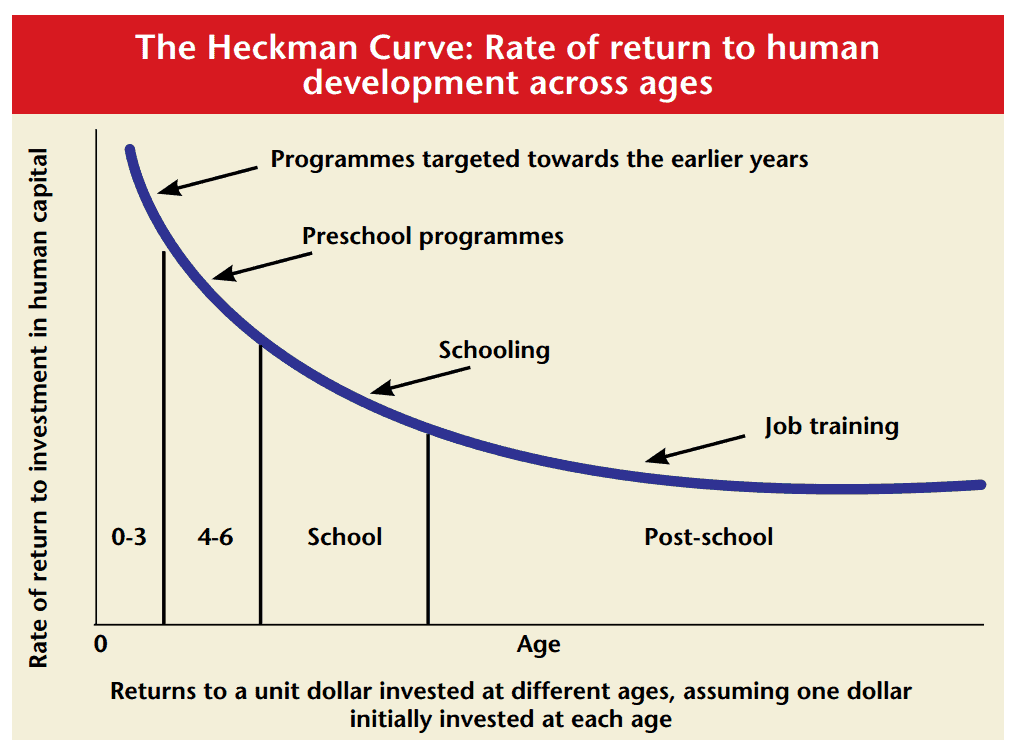

The problem of poor learning starts early. Some 54 per cent of children about to enter first grade at an aps could not pick out the correct number of objects corresponding to numbers from 10-20 (for example, picking 12 pencils from a stack of 20); and a staggering 78 per cent could not read three simple three-letter words. The neuroscience behind why this matters is clear: the preschool years are the ideal time for children to learn core skills – from pre-numeracy to phonological awareness – and lay the foundation for future academic success. It is the most impactful time to invest in these children and, as shown by the Nobel laureate James Heckman, it is the time when returns are highest on every dollar invested.

Low-income children across India are owed a solid foundation and the opportunity to succeed in life. They deserve a good preschool. Low-income parents are spending on Early Childhood Education (ECE), but getting poor quality.

Parents are sending their children to private schools (86 per cent are in APSS) and this is not going to change. Parents want the best possible education for their children and believe government schools to be of inferior quality. They also feel peer pressure to choose private schools because everyone around them is also going private, and they don’t want their child to be left behind.

They are also spending on private preschooling because they want their child to have a headstart. 95 per cent of low-income children are enrolled in preschool because their parents believe they will learn the basic academic skills (particularly english and mathematics) that can help them succeed later in life. This choice to invest in private preschooling requires investment and sacrifice from India’s working poor parents.

Consider for example a driver who earns ₹12,000 per month, and after rent and groceries has around ₹4,000 left to meet all other expenses. He is likely to be spending ₹800 from what he has left on a private preschool for just one of his children, and typically double that as most families have two children in private school. If someone falls ill, a difficult choice has to be made between buying the full set of medicines prescribed or paying school fees.

Unfortunately, what parents are getting for their hard earned money is rote-learning that leaves children reciting the same content, but with no understanding of actual concepts. Activity-based learning where children learn concepts by doing are virtually non-existent. Private preschools have no incentive to move away from rote-learning though because the markers of learning that parents are currently looking for are the wrong markers – such as whether the child can recite numbers up to 20 or sing nursery rhymes – and can be easily addressed through rote-learning. Over 95 per cent of parents are satisfied with the quality of their current preschool, despite the fact that their children are not really learning. Something needs to change.

FSG’s innovative and self-sustaining approach to improve learning outcomes

FSG, an organisation dedicated to catalyzing social change, has spent two years working on this problem through its programme to improve private early (PIPE) education. They have interviewed over 4,000 low-income parents, worked on the ground with APSS, and researched business models for delivering high-quality educational solutions. FSG has identified that there are ‘right’ markers that can easily and intuitively demonstrate to parents that their child is actually learning concepts. Parents would be willing to pay for a solution that delivers conceptual learning that they can recognise through the right markers. Encouragingly, education services companies that can provide such solutions already exist in India. The task ahead is to get them into APSS from the mid and higher-end schools they traditionally serve.

FSG has already piloted such solutions in 35 APSS to understand how they can be translated successfully into APSS: How do you sell to an APS owner? How do you deliver effectively in a school, where the teacher is untrained and there is no space for activities? These are questions PIPE is already answering. PIPE is now working with six education service companies, to get them to serve the market at scale in a commercially viable manner. This will lead to both improved learning outcomes and sustainability – so that the lives of millions of urban children can be improved without ongoing grant funding.

Scaling up the solution

AVPN, the only pan-Asian network, brings together the full spectrum of social investors from foundations to corporations, impact funds to incubators. Its members include organisations such as Shell Foundation, Omidyar Network, Oxford Said Business School, Thompson Reuters Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation amongst many others across the globe.

As CSR and philanthropies tend to work on their own, AVPN recognises that there is an opportunity to create greater impact through multi-stakeholder collaboration. To this end, AVPN is forming collectives to facilitate collaborative social investments and attention to under-represented causes with high-impact potential. Its latest report, launched during the AVPN India Summit 2017 and titled Funding education with impact: a guide for social investment in India, has identified early learning for urban low-income children as a high-priority issue to scale up.

PIPE has the potential to create impact at scale, and therefore AVPN is partnering with pipe through its Early Learning Collective (ELC), which will bring together philanthropic foundations and CSR funding in a targeted, impactful, and sustainable manner.

The ELC will help pool resources and, for each contribution of ₹60 lakh per annum, deliver improved learning environment for 1,200 low-income children; equip 32 classrooms; train 48 teachers; and reach 1,200 parents with information about high-quality preschooling. More importantly, as word of the right markers spreads among parents, the market will be on the path to transformation without the need for additional CSR funds. A truly powerful and self-sustaining innovation!